By Gary Graham Hughes, February 2021

The Carquínez Strait is a wonder of powerful tide waters that connects the San Francisco Bay with the Sacramento-San Joaquín Delta. Every salmon born in the extensive Sacramento and Central Valley watersheds will make the journey through this bottleneck of coastline on their way to the Pacific Ocean. The shores of the strait have been subject to intense industrial activity since colonization.

The Carquinez Strait is in many ways the geographical heart of the ‘refinery corridor’ that stretches from Richmond up along the north east shore of the Bay and through the strait ultimately to the last open waters of the Delta in Benicia and Martinez.

The Phillips 66 refinery on the shores of San Francisco Bay.

With concrete, rebar and steel transforming the shoreline this ecological jewel has been for more than a century industrially developed into one of the most important fuel refining centers in North America, if not the Western Hemisphere. Tankers bringing crude petroleum to the refineries from exotic destinations from around the world have received persistent climate activist attention. As California oil gets harder and harder to extract, tremendous amounts of the oil processed in the refinery sector comes from Arctic Alaska, the tropical forests of the Western Amazon, and the Arabian Peninsula. Less celebrated yet equally significant are the tankers with refined fuels departing from SF Bay for destinations around the Pacific Rim. In fact, California Energy Commission studies have shown as much as 30% of oil-based products refined in California, especially fuels like gasoline, diesel and jet fuel, being exported to foreign markets.

Regardless of the imposing structures along the shores of the Bay, or the giant tankers dwarfing small fishing boats, it is impossible to ignore the inevitable changes confronting an industry whose environmental and social pollution have exacted tremendous costs from the communities that live along the refinery corridor, as well as the global climate.

The stresses and uncertainties of what those changes might bring have been accelerated and complicated by the always turbulent circumstances of a fractured industrial empire whose foot soldiers are searching for last desperate riches.

Over the course of 2020 the pandemic hit the California petroleum refining sector hard. Prices and demand crashed, both for crude petroleum and refined products. As people sheltered at home and transportation needs were transformed in less than two weeks time, the industry suffered what they refer to as ‘demand destruction.’ People stopped driving and flying, and the consumption of liquid fuels plummeted.

In the refinery corridor of the North San Francisco Bay, which is the direct source of all the liquid fuels consumed on the North Coast of California, one refinery was forced into an immediate shut down. Shortly after shelter-at-home orders were announced the Marathon refinery in Martinez suddenly stopped processing petroleum and switched to only operating fuel storage and distribution infrastructure.

The hit to the Marathon refinery was the type of event that informed observers of the industry have been suggesting would be inevitable without integrated planning for anticipating refinery decommissioning and a managed decline of fossil fuel extraction and processing. Yet the refinery closure was still a shock to frontline communities. Along with tremendous fiscal impacts for local governments from the loss of tax revenue, the threat of sudden and unanticipated refinery shut downs carry with them massive risks of abandoned toxic industrial infrastructure in places that for all intents and purposes have long been industrial sacrifice zones.

As the pandemic ground on over the spring and into the summer of 2020, the uncertainty for communities on the frontlines that experience the day to day convulsions of a combustive industry escalated dramatically when first Marathon, and then Phillips 66, owner and operator of the massive refining facility in Rodeo on the Carquinez Strait, made announcements that they were going to convert to processing biofuels.

Experienced community organizers in the refinery corridor, having confronted for years the different industry efforts to cloak expansion plans with ‘green’ rhetoric, were immediately skeptical. As Phillips 66 rolled out an extensive public relations campaign about their “Rodeo Renewed” project, proclaiming their intent to become the biggest “renewable diesel” and “sustainable aviation fuel” refinery in the world, organizations such as San Francisco Baykeeper, Sunflower Alliance, Communities for a Better Environment, Natural Resources Defense Council and others lead the way on pressing Contra Costa County authorities, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, and the companies themselves for more information about their intentions.

As Phillips 66 intensified their campaign touting the environmental benefits of their project, concerned parties tried to learn more about the proposed feedstocks and refinery processes. Of many potential problems with the proposed project, two began to emerge as particularly problematic. The question of the feedstock was for one a major concern; while the company touted the innocuous nature of used cooking oil and waste oils as biofuel feedstock, analysis of feedstock availability reveals their dramatically limited and finite nature. Further questioning of industry reps lead to occasional transparent admittance to the inevitability of soy as a feedstock for refineries repurposed to manufacture biofuels.

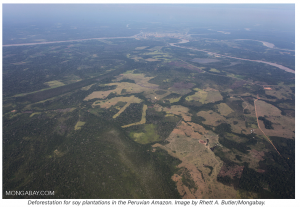

Regardless of the public relations focus on used cooking oil there is little question that the primary feedstock for these repurposed refineries would be high deforestation risks commodities like soy.

It is well recognized among biofuel industry observers that increases in market demand for soy has ramifications across distinct commodity markets, and that such increases in demand are the primary economic motors that push monoculture agriculture plantations of soy, palm and other commodities further into endangered ecosystems around the globe.

It is well recognized among biofuel industry observers that increases in market demand for soy has ramifications across distinct commodity markets, and that such increases in demand are the primary economic motors that push monoculture agriculture plantations of soy, palm and other commodities further into endangered ecosystems around the globe.

The other climate dead end trend identified by looking deeper at the Phillips 66 proposed biofuels project is the massive reliance on fossil fuels, and in particular the apparent technical dependence on fossil gas (methane) for extracting the hydrogen needed in the refining process. Calculations using Phillips 66 numbers on refinery capacity showed that the climate emissions impact from the refinery to make diesel and jet fuel from soy would be equal to or even exceed that from the process of refining fuels from crude petroleum.

There is no escaping the reality that the proposed Phillips 66 “Rodeo Renewed” project would be a high intensity greenhouse gas emissions facility.

Tangential to these concerns about the impacts from refining soy-based liquid fuels was the curious and opaque statement from Phillips 66 that to proceed with their refinery conversion to biofuels the company would need to more than double the amount of crude oil deliveries by tanker. Considering that an increase in tanker deliveries to the refinery has been fundamental to the Phillips 66 permitting requests over the last several years, watchdogs of the oil industry in the refinery corridor immediately expressed suspicions about whether or not Phillips 66 is engaged in a covert effort to use a proposed renewable energy project to surreptitiously attain their more immediate goal of bringing more crude oil by tanker ship to their SF Bay facility.

As the California Environmental Quality Act process was discretely initiated during the New Year holiday the review has thus far not received the public attention that a project of this enormity merits. In an effort to help break the silence about the refinery conversion risk, climate justice activists in Northern California are demanding that public officials join in exhorting Contra Costa County authorities to do exhaustive and thorough review of the massive array of potential impacts that arise from converting Bay Area refineries to biofuels. Processing liquid fuels from commodities based on a monoculture agriculture model that is devastating the worlds last intact forests requires close review, as does the probable fossil fuel lock in that such biofuel processing and refining would likely entail.

Dangerously, both the governors office and aviation industry consultants associated with the Bay Area Air Quality Management District have suggested that the economic and climate circumstances may require a certain fast tracking of the permitting for these refinery conversions.

Nothing could be more irresponsible than for government authorities to fail to complete the necessary and legally required exhaustive environmental review of these proposals.

As the world scrambles to understand the enormity of the climate crisis one of the greatest challenges will be to decipher and unmask the climate traps that are being paraded as solutions. There is no question that the proposed pivot in the California refinery sector to biofuels merits close attention and painstakingly thorough environmental review. Thus far the lack of reliable information is certainly raising more questions than answers.

See the Scoping letter on the Phillips 66 refinery conversion project that was submitted to Contra Costa County land use planning authorities here: https://www.biofuelwatch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Scoping-comments-Rodeo-Renewed-EIR.pdf